Built as a summer home for Richard John Uniacke, a Nova Scotian Attorney-General, the estate was prominently located along the stage coach route from Halifax to Windsor, a testimony to Uniacke’s wealth and personal achievement.

The family summered in the area as early as the 1790s, probably staying in a farmhouse on the original land grant. Construction of the new house and out-buildings began in 1813 and was completed three years later. Although he maintained a house in Halifax, Uniacke would spend most of his time living in semi-retirement at the estate until his death in 1830.

The family summered in the area as early as the 1790s, probably staying in a farmhouse on the original land grant. Construction of the new house and out-buildings began in 1813 and was completed three years later. Although he maintained a house in Halifax, Uniacke would spend most of his time living in semi-retirement at the estate until his death in 1830.

Nostalgic for his native Ireland, he modeled his property after the Irish country estates, or working farms, he had known as a child. His estate included a large family home, a number of barns, a coach house, guest house, wash house, baths, privy, hot house, caretaker's house and an ice house.

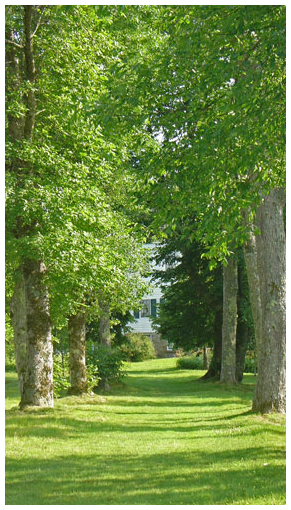

Most of the outbuildings were clustered near the main house and the barn, with the hot house in the nearby orchard, and the boat house placed at the end of a well-placed allée of trees extending from the house to the lake. Standing on the impressive portico, one could view stage coaches en route from Halifax and the sweeping vista encompassing Lake Martha and Norman Lake, with tranquil fields in the distance and an expansive garden in front of the house.

Most of the outbuildings were clustered near the main house and the barn, with the hot house in the nearby orchard, and the boat house placed at the end of a well-placed allée of trees extending from the house to the lake. Standing on the impressive portico, one could view stage coaches en route from Halifax and the sweeping vista encompassing Lake Martha and Norman Lake, with tranquil fields in the distance and an expansive garden in front of the house.

Uniacke was a gentleman farmer at heart and devoted himself to clearing and improving woodlands and wetlands, experimenting with composting materials and methods, and growing a variety of agricultural and horticultural crops. He also kept horses, cattle, sheep, pigs and poultry. He was interested in the latest agricultural methods and spent his last years as a country gentleman improving his land and growing exotic plants in his hothouse. Late in life, he planted acorns he carried back from Ireland. Today, visitors can still see some of the mighty oaks he planted.

The fields and pastures may have been fenced, but, as the land was improved, hedges were planted and roads and open fields were edged with dry-stone walls and lined with trees. Trees were also used to form gateways, and planted in the fields to add to the picturesque beauty of the place. The brook was improved with stone walls and willow plantings.

The fields and pastures may have been fenced, but, as the land was improved, hedges were planted and roads and open fields were edged with dry-stone walls and lined with trees. Trees were also used to form gateways, and planted in the fields to add to the picturesque beauty of the place. The brook was improved with stone walls and willow plantings.

Stone walls have been discovered in what is now forest, evidence that many of the 100 acres cleared for Uniacke have since returned to the wild. His efforts to create a self-supporting estate were not successful due to the unsuitability of the land for farming, but the house remained a popular summer getaway for the family for generations.

The grounds of Uniacke’s estate were designed in the English Landscape Garden style which was popular in the early 1800s. A key feature of this style was a long, uninterrupted view, or vista, and the one at Uniacke’s estate was unrivaled in its day.

Sheep, grazing in the distance, contributed to the idyllic scenery one could admire from the portico of the grand house. To contain the sheep and keep them from wandering onto the lawns, Uniacke constructed a natural-looking barrier called a haha wall--rather than building a fence--to avoid obstructing the panoramic view. Visitors to Uniacke Estate can still view this haha wall, one of only two known to remain in Canada.